Five months have passed since the start of the uprising in Iran. Hundreds of protesters remain behind bars, facing long-term sentences, court hearings, and uncertainty over their trials. On February 5, 2023 however, Gholamhossein Mohseni-Ejei, the head of Iran’s judiciary, announced that tens of thousands of protesters and other prisoners would be pardoned as part of an amnesty in observance of the 44th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution. There are, however, certain conditions regarding pardons and commute of sentences. For example, those charged with “enmity with God or Corruption on Earth” which could carry the death penalty, those charged with “espionage” or those facing charges of “direct links with foreign intelligence services, murder, or attack on governmental, military and public sites, through vandalism or arson” will not be eligible for pardons, or early release under the amnesty scheme.

Rights groups had estimated the number of those arrested in relation to the protests at around 20,000, with over 5000 names confirmed. But recent commentary from those close to the government indicates that the severity of crackdowns and widespread arrests were in fact much higher than previously believed. For example, some political figures celebrating the benevolence of the state on social media for releasing prisoners as well as a February 7, 2023 report published on a website called Roydad-24 have claimed that up to 100,000 prisoners would benefit from the amnesty scheme, with 30,000 of them having been arrested in relation to the recent protests.

Initially there was much speculation about the reason for the widespread amnesties. Some rights groups dismissed the amnesty program by claiming that it would not benefit political prisoners or those arrested in protests. But the amnesty has in fact benefitted a large number of prisoners, the exact figures remain unknown. For example, according to Femena’s sources, 35 of the 61 political prisoners in Evin’s women’s ward and 43 of the 49 women political prisoners in Qarchak prison have been released following the amnesty scheme, with many of them being women human rights defenders.

Some observers believe the amnesty was provided at an opportune time when protests had died down, as such the state and security forces were not experiencing a direct threat. If the protests were continuing in their full force, these analysts believe, then amnesty would not have been provided.

Other factors, according to observers, have also contributed to the decision on amnesty. For example, the high number of detainees and insufficient prison capacity to accommodate the current prisoners has been cited as one of the main reasons behind the recent amnesty. According to reports from those recently released, prison conditions have been so overcrowded that prisoners often could not find enough space to sleep, many were suffering from hunger and prisons were unable to feed inmates.

Others have speculated that the amnesty was a preemptive move intended to prevent the formation of networks of dissent among prisoners and their families. In fact, political prisoners have long organized to express dissent, by issuing statements, staging sit-ins and resisting injustice. The large number of protesters arrested, many unversed and inexperienced in political activism, being held alongside more experienced activists, allows for the formation of connections between like-minded individuals who are discontent with the status quo. These prisoners can continue their their connections and collaborations long after being released which would prove problematic for the state.

Further, family members of political prisoners were also connecting during their visits to the prison and organizing in support of their imprisoned loved ones. For a state and security system long opposed to the formation of civic and political networks, prisons were serving as a breeding ground allowing dissatisfied citizens to find one another and organize.

While the amnesty scheme has benefited a number of political prisoners and many protesters, it is still criticized by rights groups for pushing those who are released to admit to their guilt in writing, express repentance and commit to not engaging in any form of social or political activism upon release. This places an undue burden on those pardoned, because if they are perceived as violating the terms of their release they could be taken back to prison. So, they may be free, but continue to be at imminent risk of re-arrest. Other prisoners have been asked to post bail as a condition of their release.

It should be noted that some who have refused to sign such statements or to post bail have still been released, but their numbers are limited. Furthermore, better known political prisoners, like Farhad Meysami, who refused to post bail or sign statements of repentance was still released. Farhad Meysami, who was serving a prison term for opposing the mandatory hijab, made the news on February 2, 2023, when he released pictures of his emaciated body due to a hunger strike. While his release is welcome, he along with several other notable political prisoners who were released under the amnesty scheme, had already served the bulk of their sentences. Others such as Yasaman Aryani and Aliye Motallebzadeh were also released after serving a substantial portion of their sentence.

Meanwhile, many WHRDs and HRDs facing serious charges or already serving long prison sentences have not been able to benefit from the amnesty scheme. This includes those arrested in relation to the recent protests, such as journalists and WHRDs Niloufar Hamedi and Elahe Mohammadi as well as those who face other charges like Bahareh Hedayat, Narges Mohammadi, or Vida Rabbani.

The release of so many prisoners, especially ordinary protesters with no or little experience of prior political and social activism, also increases fears about the fate of those left behind. It is clear that the state views those not released as a serious threat and as such, their welfare is in danger. Fourteen protesters remain on death row and are in imminent danger of execution. In the past five months, four protesters, Mohsen Shekari, Majidreza Rahnavard, Seyed Mohammad Hosseini, and Mohammad Mahdi Karmi, were executed in short trials that failed to meet due process standards. So the need for human rights groups to remain vigilant and focused on the situation of prisoners is as critical as ever.

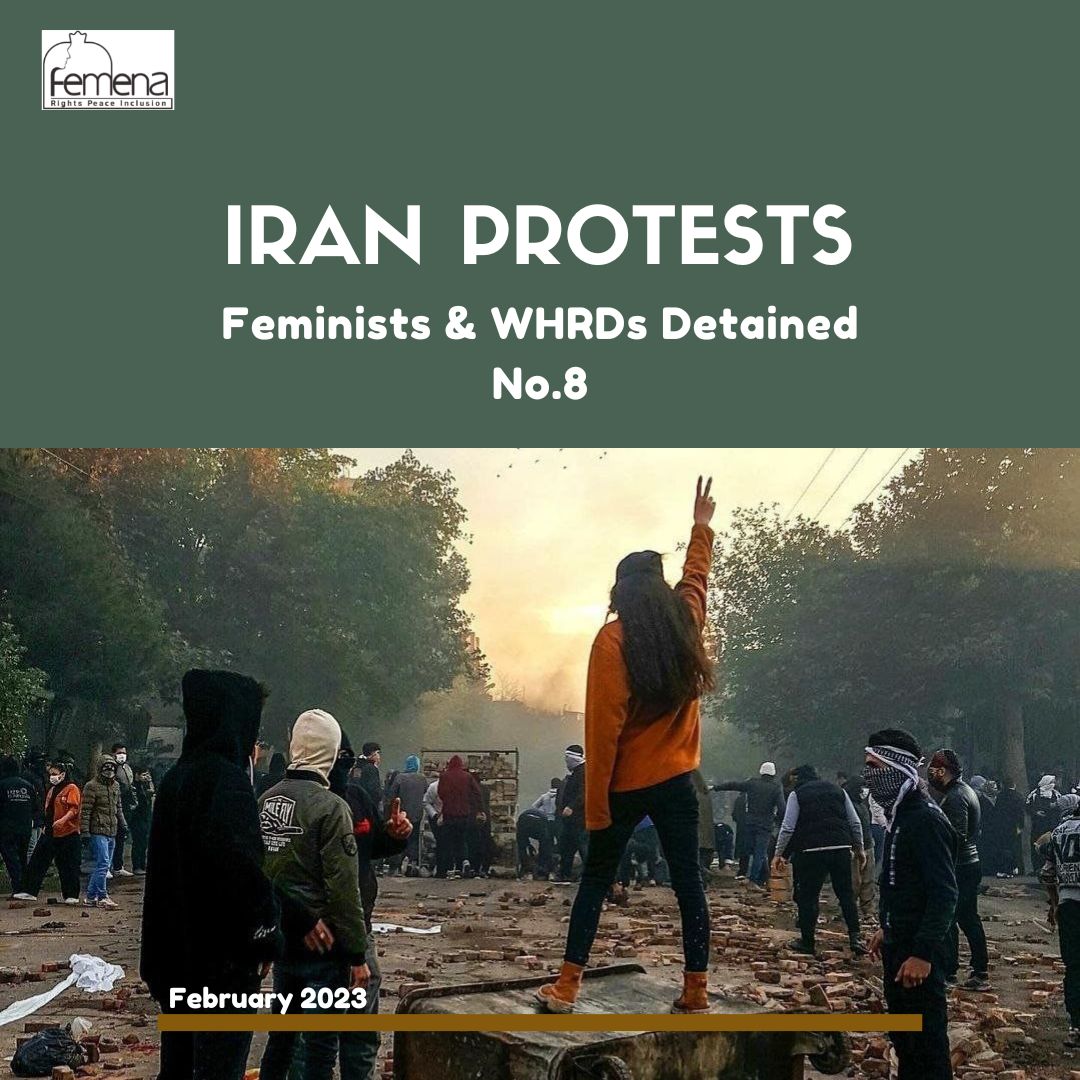

This current report, the 8th in the series, highlights the arrests, intimidations, and suppression of 51 imprisoned WHRDs, arrested in relation to the protests. Some of these prisoners remain in prison; some have been temporarily released on bail, awaiting their trial, and others have received their sentences. Femena aims to document the cases of WHRDs arrested in the aftermath of the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising, with the aim of raising awareness and ensuring that their cases are followed by international bodies, rights groups, and feminist movements who can provide solidarity and continue to demand their release.