Source: Frida

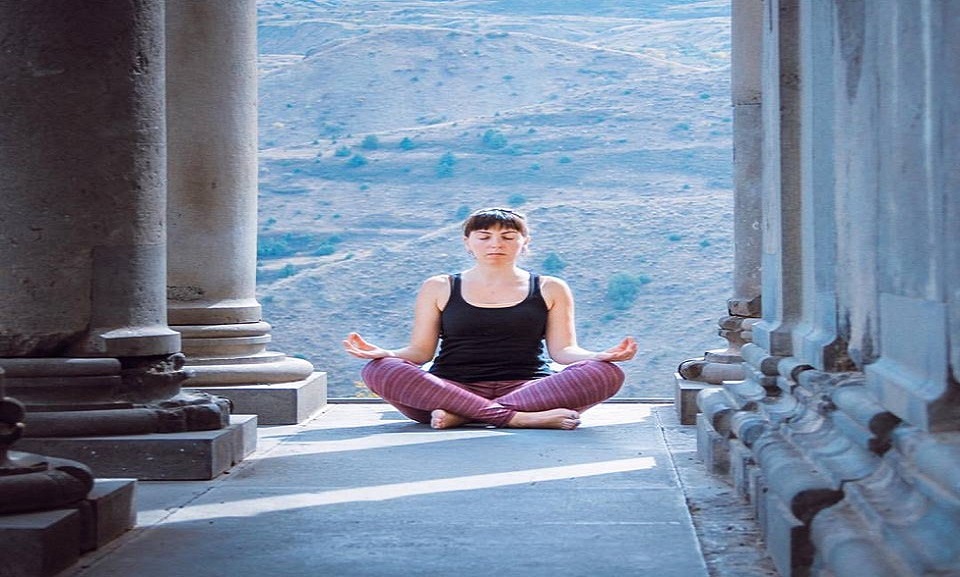

Hasmig Tatiossian is a young feminist activist and the co-founder of Stega: A Perfect Union, a yoga and meditation initiative intended to promote self-care among social change makers in Armenia. We got in touch with her to hear more about her journey of creating a space like Stega, the context from which it operates and her own understanding of the sense of “self” and caring for it:

Tell us a little bit about yourself! Where are you from? How did your feminist journey begin?

I was born and raised in Los Angeles to Armenian parents and within a tightly-knit Armenian community. Both my parents had immigrated to the US in the 1970s: my mother from Armenia, and my father from Syria. Culturally, boys are often given a lot more freedom than girls, but since I was one of two daughters — and my parents weren’t too conservative in our upbringing — we weren’t subjected to favoritism. We were raised to believe that through a good education, we could do or be anything we wanted to be. Even though girls were expected to do well in school, I felt from a very young age that boys were favored — something that deeply irritated me. In hindsight, this recognition is when I’d say my feminist observations began, but I wouldn’t label it that as a child. In fact, my “Armenianness” was the most dominant part of my identity, not my “girlhood.”

My college years were also the first few years of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, and my identity was being refined much more as a progressive than a feminist. I studied human rights and genocide, knew about wartime gender based violence, but feminism wasn’t a lens I looked through to understand myself, my community or the world at large. It wasn’t until graduate school when I tasted that bitter, silent entitlement from some of my male peers. In so-called “hard” international relations courses (versus “softer” human rights courses), they would dominate the conversation, interrupt, and speak with a knowing air. This sense of entitlement and superiority was real, but it was hardly spoken of. The final turning point came when I took a course about women’s movements. We got to the heart of so many issues faced by women across the world, and that course changed the direction of my life. I subsequently decided to make women and peacebuidling the focus of my thesis, traveled to Armenia to do research and worked there at the Women’s Resource Center. Although the roots of my feminist journey go back to childhood, it was at this point in my life when feminism became grounded in knowledge and activism.

Tell us a little bit about your project! What is Stega and what is its objective?

Stega: A Perfect Union promotes self-care through the practices of yoga and meditation. It specifically targets social change makers who are susceptible to exhaustion and burnout. The Stega model of self-care seeks to teach participants how to carve out time for their wellbeing, in order to care for themselves, build resiliency and make their work sustainable. Through the linking of mind, body, and breath, we invite participants to develop compassion and loving kindness towards themselves, practice mindfulness, and maintain self-awareness. Some of the other benefits that come about are increased focus, clarity, renewal of a sense of purpose and the forming of community.

How did the idea of the project “Stega: A Perfect Union” originate? What pushed you towards working on something like this?

Stega: A Perfect Union was a response to a need I observed: the frequency of burn out and lack of self-care among my friends who worked at NGOs in Armenia. I watched from afar as they ran organizations on tight budgets and faced discrimination for defending the rights of marginalized communities. Some also worked one-on-one with highly traumatized populations, like survivors of gender based violence. Sometimes, one person faced all three of these obstacles.

Personally, yoga and meditation were practices that were crucial in my life as I worked through overcoming a traumatic experience, and I knew their transformative powers. I wanted to introduce these practices to those who were working so hard to make a positive impact in Armenia, in hopes that they would start taking care of themselves. My project partner and best friend, Armen Menechyan is a yoga teacher, and he has also used this healing practice to overcome difficult life experiences. We teamed up and decided to run a pilot project in Armenia. There, we ended up working with participants from over 20 organizations.

How did your own self-care journey begin? When did you first realize this is something that you want to focus on, personally and politically?

Often in life, we don’t make big changes unless we’re thrust into the fire. For me, it was the breakdown of a 10 year relationship and a separation from my husband. This really shook me. I hit rock bottom. It brought to question so much of what I had believed in, it rattled me at my very core, and I realized that, having become just a shell of myself, I had a lot of rebuilding to do. Luckily, I had had a meditation practice for several years, and so my meditation cushion became my companion. I knew that no matter the depth of the heartbreak at any given moment, I could reunite with my breath, and that place, that spaciousness was the safest place I could be. Even if what I was experiencing was grief, loss, or anger, I could zoom in on a feeling and embrace it, with an awareness that it had something to teach me. It was part of the human experience that I was temporarily being given access to, and it presented an opportunity for growth. The awareness of breath brought deep peace even after turmoil, and it held the promise of new beginnings. Every breath was an opportunity to shed, build, learn, and be. This was the first teaching in self-care that came through meditation: accepting the current unavoidable situation as is, sitting in and with the darkness without a need to change or judge it, accepting it as a teacher, and knowing that there is always a new dawn.

One of my first big steps was to move from the east coast to California, where my family and many of my friends lived. I decided to drive across the country, and this proved to be one of the best decisions I’d ever made. For two weeks, I fell into the embrace of nature. With a few exceptions, I stayed away from big cities, and focused instead on small towns, near mountains and bodies of water. I read, wrote, swam, hiked, and cried. The vastness and diversity of the landscapes allowed me to breathe more deeply. I felt so intricately connected to nature, and realized that every lesson I needed to learn was right there, being offered by her. How blessed I felt to have been carried and held by the earth itself. The solitude of those two weeks was invaluable beyond measure. These were the next teachings in self-care: solitude and nature, and better yet, solitude in nature.

Shortly after I arrived to California, Armen encouraged me to start going to yoga classes. Having briefly experienced the power of yoga several years prior, I knew intuitively that that’s what I needed. Yoga brought me back to my body in ways I never knew I was missing. I discovered muscles the existence of which I had not known. I learned to befriend my body and grant it as much importance as my head. Having been a cerebral person all of my life, my body had become relegated to a vessel that carried what I needed for survival, and a part of me with which I had no authentic relationship. Through yoga, I found the “stuck” places, the places that held so much of the pain I was working through. I learned patience and acceptance; experienced joy, release, and deep gratitude. I grew stronger, and I let go even more of the need to control, trusting the mysterious unfolding of life. I began to feel loving kindness towards myself. These were some of the many self-care teachings that came through yoga.

Although all of these experiences are deeply personal, what emerges out of this inner work is a connection to a source, that which binds us to one another and to all other beings. As we grow more rooted and centered into our Selves, we become more compassionate towards others. Perhaps we start seeing suffering through a different lens and we develop a heightened empathy towards all creatures — including those we deem “inferior.” As social change makers, we may even question the power dynamics that we may have accepted as part of our work, i.e. “helper” v. “helped.” We may start to recognize that these roles we play may shift and reverse at any time. We recognize and begin to question our own deeply held beliefs, stereotypes, and assumptions. The more this inner expansion occurs and the more we narrow the spaces we’ve created between each other, the more compassionate and courageously vulnerable we become, the more we’re inclined to serve others, the more we may seek to alleviate suffering. Invariably then, we enter the political. On a mass level, alleviating suffering necessitates recognizing unequal socio-economic structures, the effects of our destructive choices on the environment, the consequences of patriarchy, etc. On an organizational level, it may bring to question styles of leadership and hierarchy. I think the deeper we move into our inner work, the more we can contribute to building authentic, non-hierarchical communities, formed on the basis of doing good for good’s sake. On a personal level, we journey towards the best versions of ourselves — often slowly, sometimes falling face down — in forgiveness, humility, and love. This way of being, in a world so consumed by materialism, superficiality, and quick results is, in part, political.

Do you think self-care is a feminist issue? Why or why not?

First, it is important to note that we can’t intentionally care for a “self” we don’t understand. To care for the self, one must first be in the process of becoming acquainted with that self and approaching the Self. Self-care isn’t just about taking the time out of one’s day to watch a movie, go to a yoga class, or get a massage. It can be any one of these things, but these don’t get to the root of it. Self-care requires sitting with yourself, your pain, dreams, fantasies, neuroses. It’s about becoming aware of what Eckhart Tolle calls your “pain-body,” which he describes as “the accumulation of old emotional pain that almost all people carry in their energy field.” It’s about watching your mind tell and re-tell the stories that make up your sense of “self” — stories often based on fear, insecurity, and judgement. In this light, self-care is for everyone.

However, Tolle also describes a collective pain-body that is created by generations of suffering. We can talk about a collective women’s pain-body brought upon by a patriarchal and misogynistic culture that has inflicted physical, psychological, and emotional pain. As women and feminists, then, self-care takes on even deeper layers of significance. In societies where women are oppressed, there is a collective pain-body. We’re working through centuries of the objectification of women’s bodies, of hardened gender stereotypes, of unequal access to jobs, discrimination, and violence. These lead to all sorts of personal and social ills, ranging from feelings of shame and guilt — when a woman takes an hour to do something healthy for herself because she “should” be doing something for her family instead — all the way to violence against women.

What is missing in feminist conversations around self-care? How can we help each other prioritize it, as committed activists?

I’ll note what I think self-care shouldn’t be. While practices like meditation can really sharpen focus and lead to increased productivity, I don’t think we should think of self-care as a means to making ourselves more productive. Let’s accept these as favorable side-effects, but not the sole reasons we sit in meditation. On the other hand, as all extremes are unhealthy, self-care shouldn’t be used as code for laziness or a source of distraction from really sitting with our messy, complicated, beautiful selves. An occasional night of drinking in order to escape your troubles may feel good in the moment (go for it, no judgement here), but let’s not define it as self-care.

We can help each other prioritize self-care by putting it at the forefront of our organizations’ agendas. We also need to make self-care accessible. Yoga classes, body work, or therapy, for example, can be financially inaccessible in many parts of the world. We should be allocating funds to enable self-care within our organizations. Additionally, let’s start campaigns that eliminate the sense of shame or guilt that many women experience when they decide to set time aside for themselves. Until we have the language to describe this and speak openly and deliberately about it — as we simultaneously offer more access to self-care practices— it will be an issue that remains on the back-burner. Not only is this necessary for the good of each individual, but it’s also for the health of the collective. Ultimately, aren’t we all in this together? If I’m feeling healthy and working sustainably then that’s the energy I’m going to bring into the workplace, family, and around friends, and that’s better for everyone. We can impact each other in the subtlest of ways; the wellbeing of one can impact the wellbeing of another.

Lastly, let’s watch out for another. If we notice our friend or colleague burning out, let’s bring it up compassionately. Let’s make it acceptable to need help, to need a break. We need to maintain healthy spirits, bodies, and minds, and this would be so much more sustainable with support. Let’s stitch self-care into the very fabric of our organizational/community cultures. We’ll all be the healthier for it!

Thank you, Hasmig, for unpacking your journey and self-care conversations with us!