By Azadeh Moaveni and Sussan Tahmasebi

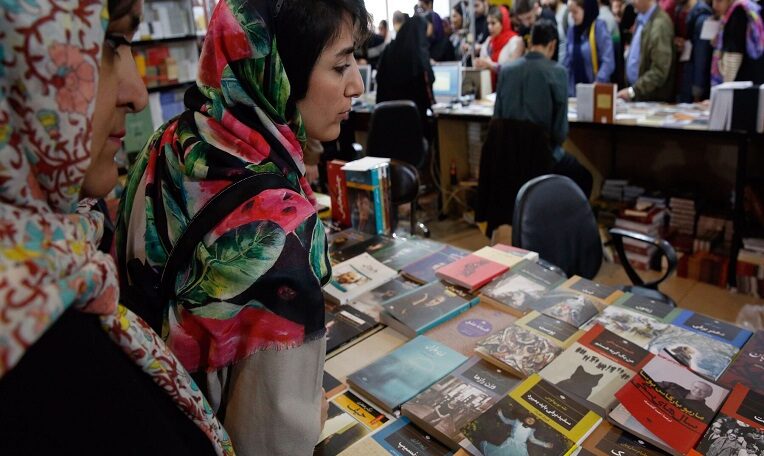

The economic slump in Iran after the reimposition of sanctions by the Trump administration is tearing away at the fragile gains Iranian women had made in employment and education.Credit…Arash Khamooshi for The New York Times

A few weeks after the Trump administration withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal in May 2018, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo condemned “brutal men of the regime” in Tehran for oppressing Iranian women who were demanding their rights.

“As human beings with inherent dignity and inalienable rights, the women of Iran deserve the same freedoms that the men of Iran possess,” Mr. Pompeo said.

But the Trump administration then dealt a tremendous blow to Iranian women by reimposing sanctions on Iran, restricting oil sales and access to the global banking system, and pushing the economy into a deep recession.

Since the spring of 2018, the Iranian rial has lost 68 percent of its value. In March 2020, inflation hit around 41 percent; today it hovers around 30 percent. In the same period, the gross domestic product shrank by 6.5 percent, and unemployment stood at 10.8 percent. The sanctions scuppered one of the nuclear deal’s key dividends: the foreign investment and job creation that was set to accompany the opening of Iran’s markets to the world.

The decimation of Iran’s economy is unfolding in the lives of the very constituency that has been working for reform and liberalization, and in whose name Mr. Pompeo and other leading American officials speak: middle-class Iranian women. The slump is tearing away at their fragile gains in employment, upper management positions and leadership roles in the arts and higher education, while reducing their capacity to seek legal reforms and protections.

Iranian women outnumber men in university enrollment but they often graduate to find that employers prefer to hire men.Credit…Arash Khamooshi for The New York Times

When the sanctions hit, Mahsa Mohammadi, a 45-year-old editor and language teacher in Tehran, was saving to pay for a graduate degree in education at a university in Istanbul. Her rent in Tehran doubled because of inflation, and she was forced to move with her young son to a small city with no cultural life.

Inflation continued rising; the rents doubled again. Ms. Mohammadi lost most of her income from English tutoring. No one could afford language classes anymore. She could then no longer afford even the small city. She moved to a cheaper, conservative hamlet near the Caspian Sea where people look down on divorced mothers. Studying abroad is now an increasingly elusive dream.

“All our demands and hopes have whittled away,” she said. “The pressure is unbearable.”

As the Biden administration explores re-engaging with Iran, some of those who oppose an American return to the nuclear deal, even as a basis for negotiating an expanded agreement, are also vocal in their support of Iranian women’s rights. In Congress, the argument that women’s rights should inform U.S. policy has particular traction. Yet members of Congress have on occasion spoken at events organized by the Mujahedin-e Khalq, a controversial Iranian opposition group that has hardly been a champion for women’s rights, even those of its own female members.For many women in Iran, hard-line American arguments for regime change and perpetual pressure fail to capture the complexities they have to grapple with. Cries to support human rights from champions of sanctions sound hollow when those sanctions dismantle a country’s economy and the livelihood of its people.

The Biden administration should acknowledge this reality as it battles domestic and congressional ambivalence toward renewed diplomacy with Iran.

Iranian women have been agitating for more rights and democracy for decades, and their triumphs against the establishment’s most doctrinaire restrictions have been led by middle-class activists. Often viewed as the primary engine of social change, middle-class women have seen their lives and hopes crushed by the Trump administration’s sanctions, and it is hard to see what the United States gains by this devastation.

Today, the “middle-class woman” in Iran is a disappearing category. Although women outnumber men in university enrollment, they often graduate to find that employers prefer to hire men.

U.S. sanctions and Covid-19 sent women’s employment rates tumbling in Iran. Credit… Arash Khamooshi for The New York Times

Women’s employment rates had increased in recent years, despite these barriers, but the layered shock to the Iranian economy from sanctions and Covid-19 has made them lose ground disproportionately.

From March to September 2020, with the coronavirus pandemic raging, men lost 637,000 jobs while women, whose work force participation is a mere 17.5 percent, lost 717,000. As Iranians resumed work in the fall, the job losses by men were reversed, while women’s employment rates continued to decline.

While lost aspiration is hard to measure with data points, women’s lagging production and representation in a number of sectors, including a cultural sphere dominated by men, has worsened since Mr. Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign.

A case in point is a publisher in Tehran who specializes in historical nonfiction. One of her more successful releases recently was a book titled “The Etiquette of Disciplining Men,” originally written in the late 19th century by an unknown woman. (This book was a rejoinder to an anonymously written patriarchal treatise called “Disciplining Women.”) In the past two years, the publisher’s list has shrunk every season, and she has halved every book’s first print run.

The cost of paper has always bedeviled Iranian publishers, but sanctions-fueled inflation has pushed prices up and limited stock. The publisher has stopped using sparkly paper for the covers to control prices, but still fewer people are buying books. “People are moving closer to the poverty line, they’re spending on meat and diapers,” said the publisher, who asked not to be identified. “We’re trying to lower prices, but we also can’t give books out for free.”

During President Hassan Rouhani’s tenure, the state censors had been granting publishing permits more liberally. Many of these books were translated by female translators working from home. Some translators, who could once earn $700 to $3,000 per book and produced two books a year, now have no orders at all.

The cost of paper has always bedeviled Iranian publishers, but inflation caused by American sanctions has severely pushed prices up and limited stock.Credit…Abedin Taherkenareh/EPA, via Shutterstock

Even in movies, the one industry that has flourished in Iran whatever the national currents, women are now faring poorly. Independent female filmmakers have long struggled to cobble together financing and to get approval from state censors for their work, especially when it deals with social taboos and legal injustices. Many of them relied on European cultural institutions for financing.

“These days, even if they manage to get official permission, sanctions block the transfer of funds from abroad,” explained Fery Malek-Madani, a curator and filmmaker whose 2018 film, “The Girls,” is a journey through girls’ primary-school classrooms across Iran.

The isolation of Iran’s movie industry has forced filmmakers to reorient themselves around national television broadcasters. These networks churn out ideological products in line with the state’s unenlightened gender norms, with women cast in subservient roles and deferential to men, their guardians and protectors. Some even promote child marriage and polygamy, practices that are rejected by the majority of Iranians.

Amid the intensified conflict with the United States, Iran’s security establishment has emerged as a major producer of blockbuster television and film centering on the prowess of the Revolutionary Guards and its intelligence services. Iran is awash in sophisticated domestic versions of “Homeland,” and deprived of the self-interrogating, subversive cinema that once allowed society to have a public conversation with itself about gender, culture, marriage and power.

The economic downturn has caused a generational shock to women’s lives and political prospects. Fatemeh, who works with survivors of domestic violence, explained that disappearing incomes and rising expenditures have pushed women back into abusive living conditions. Fatemeh, who asked to identified by her given name, also said that many of her young and single colleagues who had persuaded their families to let them live independently, have been forced to move back home by shrinking, unstable incomes and soaring rents.

Trying to stem their slide into poverty, Iranian women can’t pay the same attention to advancing legal rights and deeper political change. “Activists are struggling to survive,” explained Shiva Nazarahari, a prominent activist, who left Iran two years ago. “If they do end up with a bit of time at the end of the day for their activism, they are often too exhausted and preoccupied with economic survival to be effective.”

Iran claims to have manufactured its own coronavirus vaccine and named it “Fakhra” after Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, the nuclear scientist, who was assassinated near Tehran in November.Credit…Arash Khamooshi for The New York Times

In recent years, authoritarian forces in Iran that are keen to suppress civil society through arrests and intimidation have become stronger. And the Trump administration’s tainting embrace of Iranian women’s rights has also cast greater suspicion on women’s activism. Hoda Amid, a lawyer, was sentenced to eight years in prison for conducting a workshop on the rights of women in marriage. Ms. Nazarahari notes such sentences have become far worse than they tended to be in the past.

With Washington and Tehran caught in a diplomatic standoff, the Iranian people await relief. A sequestered and choked off Iran is functioning effectively as a state at war, dimming the prospects for its women.

“The pressure on women, on the middle class, is utterly oppressive. I just don’t find the justifications for sanctions at all persuasive, certainly not from a feminist perspective,” said Faezeh Tavakoli, a historian with the Institute of Humanities and Cultural Studies in Tehran. “You can’t tell people, ‘Starve and then seek freedom.’”