By Sussan Tahmasebi

For decades Iranian women’s rights activists have worked to raise awareness about violence against women and to eliminate it. From holding workshops, to public awareness campaigns, to advocacy for reform of laws, elimination of violence against women has been a major priority of women’s groups in Iran. In fact, when rights activists started their awareness-raising decades ago, it was difficult to talk about violence, as officials often interpreted it as an attempt to damage the image of the country. So when in November 2017, a bill drafted by the office of the Vice President on Women and Family Affairs, was sent to the Parliament for ratification, women’s rights activists were both excited and concerned. The concern stemmed from the fact that the drafting process was largely non-transparent. The bill submitted to parliament was never made public and civil society, despite years of advocacy and expertise on elimination of violence against women, was not allowed an opportunity to provide input into the draft.

According to some rights advocates interviewed, a group of experts were consulted in the drafting process and those spearheading the drafting process had legal expertise and years of experience in rights advocacy on behalf of women. Still the non-transparent process and lack of info on the contents of the bill has left many women’s movement activists critical that their expertise has not been appropriately utilized and concerned about the contents of the bill.

Veteran rights activist Jelve Javaheri says publication of the bill is important because it promotes discussion of the issues. “This is a process through which further awareness about the bill and the need to eliminate violence against women can be raised. In this way, citizens can understand the positive impacts of such a law on their lives and along with civil society speak up in its defense, if it faces opposition. But if there is no information published, it becomes difficult for civil society or the public to support such legislation.”

Contents of the Bill

Ashraf Geramizadegan, Legal Advisor to the Office of the VP on Women and Family Affairs, involved in the drafting process, explained in an interview* with the Iranian Students News Agency, that the bill includes provisions on prevention, protection and support for women facing violence. According to the interview, the draft law, includes three sections outlining overall concepts and aims; responsibilities of various government agencies in prevention, protection and provision of support services to women; and crimes, penalties and judicial procedures. The bill, according to Geramizadegan, defines violence against women as “any intentional act causing physical, emotional, reputational or character harm to a woman or any act restricting a woman’s legal rights or freedoms.”

Criticisms of the Bill by Conservatives

Despite the fact that the contents of the bill have not been made public, it has been widely criticized by hardline forces. One of the main criticisms of the draft law is that it over criminalizes and seeks to unnecessarily prosecute men. Other conservatives have criticized the bill as being Western in orientation or driven by Western and feminist demands.

This is despite the fact that both the Office of Women and Family Affairs, and the Parliament have taken excruciating steps, including maintaining a low-key approach in the drafting and adoption processes, so as to obtain buy-in from conservative bodies. Additionally, the drafting process, which was criticized for being too long, took measures to coordinate closely with the Judiciary as well as religious leaders. Since going to parliament the bill has been submitted again to the judiciary for input and religious leaders in Qom have also been consulted. Each of the many rounds of consultations and discussions has resulted in revisions, adding to the lack of clarity on the provisions of the bill and fears among rights advocates that revisions have stripped any real supports for women.

Ameneh Shirafkan, journalist and long time women’s rights activist, explained that: “according to sources close to the Office of Women’s Affairs, the bill in its initial version was progressive and addressed longtime concerns of women’s rights activists. But since its drafting the bill has been altered and amended numerous times, by the judiciary, based on comments by conservative clerics in Qom, and by Parliamentarians.” Shirafkan is not certain or hopeful that after so many revisions, the bill will still include progressive measures in support of women facing violence.

Civil Society Efforts

Rights advocates in the Campaign to Prevent Domestic Violence (PDV) however say that it doesn’t matter what was in the bill or what is currently in the bill. A good law is our ideal goal, explained Jelve Javaheri who is a member of the PDV Campaign, “but a law that is top down and is not based on a process of consultation and broad consensus building with civil society and the public, will fail to raise the awareness necessary to change behavior and ensure compliance and buy-in.”

The PDV Campaign however has worked to build consensus and awareness by holding consultations in several provinces across the country with over 200 individuals. The Campaign has also collected over 300 stories by women about their experiences with violence. Further, in collaboration with a group of Lawyers, who have examined laws in Asia and Africa as well as other countries, a draft civil society bill designed to eliminate domestic violence was developed. This group wants lawmakers to consider the civil society law and engage with rights activists in a meaningful way before adopting legislation designed to eliminate violence against women.

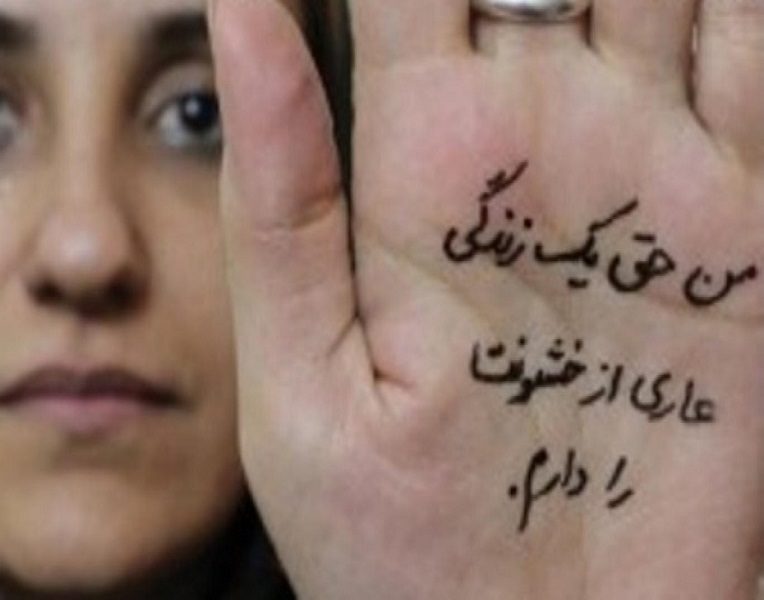

To this end, the PDV Campaign put forward a statement on the occasion of the International day to Eliminate Violence against Women on November 25, 2018, signed by over 1700 rights activists and practitioners, demanding a comprehensive law to eliminate violence, achieved through a broad based process of consultation. The group took their demands to MPs, by holding a protest in front of Parliament on November 25, 2018. While the protest was broken up quickly, some female MPs committed to passing legal protections for women, expressed interest in meeting with women activists on the issue.

The fate of the bill to Prevent Violence against Women remains illusive and unclear nearly six months later. Perhaps women’s rights advocates in government may do well to consult with civil society and the general public before proposing or advocating legal measures, in the hopes that public support can help counter opposition and push through measures designed to protect the rights of women.